Permanent Collection Asia

Design: Peter Noever

Previous Image

Permanent Collection space 1993–2013

Making centuries of cultural transfer between Asia and Europe traceable through a line-up of exemplary exhibits from the MAK collection is the goal that informs the reinstallation of the MAK Permanent Collection Asia. Since 2007, the exhibition room has been used for temporary shows about individual aspects of the comprehensive collection. Opening on 26 October 2012, the new presentation again provides a survey of the total range of the MAK’s fascinating Asian collection, which—comprised of holdings of 25,000 objects from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Iran, and Turkey dating from the Neolithic period up to the present day—ranks as one of the most comprehensive collections of Asian art in Europe.

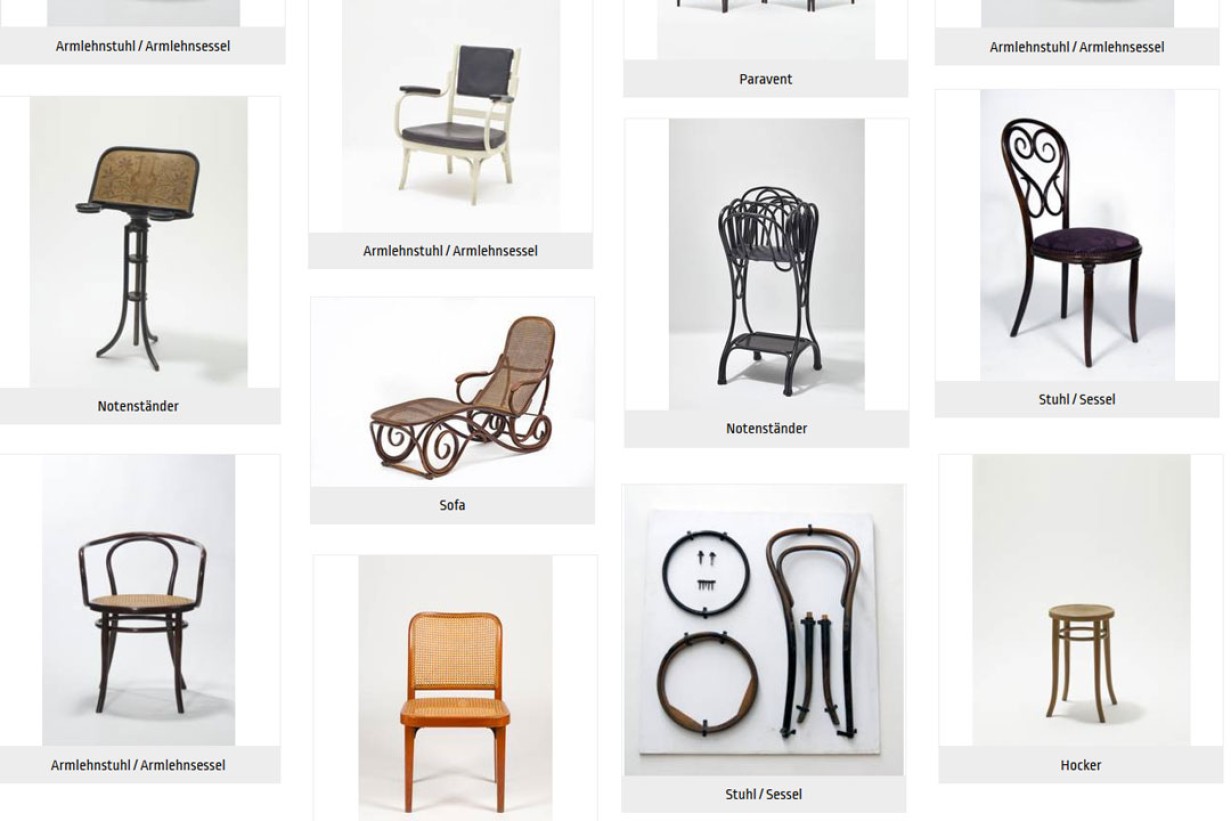

Chinese porcelain, Japanese lacquerwork, Japanese colored woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) and Japanese dyeing stencils (katagami) make up the core of the MAK Asia Collection, which—like all comparable collections—in itself constitutes an instance of Orientalism: after all, the objects assembled here were all collected by Europeans and thus are representative of distinctly European tastes. Divided into forty small chapters, the reinstallation invites visitors on a time travel through Asian art history, which puts the “masterpieces” on exhibit in an art-and-cultural-history perspective.

Archaeological objects from China and Vietnam, particularly grave figures from the Han (206–220 AD) and Tang periods (618–907 AD), which already evidence contacts with Iranian art, mark the beginning of the reinstalled exhibition. Religious objects, sculptures, but also paintings indicate a paradigmatic transformation that went along with Buddhism, which emerged in the Tang period and eventually eclipsed the funeral cult. The richness of variations of Chinese and Japanese ceramics developed in an interaction with Western cultures and is demonstrated by examples from various epochs. Precious tea bowls and delicate ceramics document the arts-and crafts production of the early Song Dynasty (960–1279). From the time of the Mongolian rule in the Yuian Dynasty (1271- 1368), porcelain with cobalt-blue painting was much sought after by rulers’ courts throughout Asia, not least as a consequence of close contacts with the Islamic world. Like the early blue-and-white porcelains lacquer works oft that period show the Islamic horror vacui decoration.

It was only on the time of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) that the trade radius for Asian articles was extended to Europe. Royal and later also bourgeoisie households provided themselves with goods and wares from East Asia; Chinese porcelain became the utility tableware of a refined lifestyle. One unique example of this cultural blending that occurred from the 16th century is a tabletop from the library of Ambras Castle, Tyrol, which presumably was made by Chinese artisans in the South-Indian port city of Cochin (today: Kochi, Kerala) in a mixed Sino-European style on an order from Portuguese traders. Increasing demand for exported luxury products and East-Asian fashion influences on Europe informed the term “chinoiserie.” However, this well-known phenomenon in fact meant a reciprocal exchange: for European culture also was received with enthusiasm in China; Western artists and scientists were again and again invited to stay and work at the Imperial court in Beijing. Traditional Chinese art of the 18th century is documented in the exhibition by a unique vase, cut in Chinese style from a single block of jade (nephrite), whereas a silver and enamel globe is the central exhibit that stands for European influenced pieces.

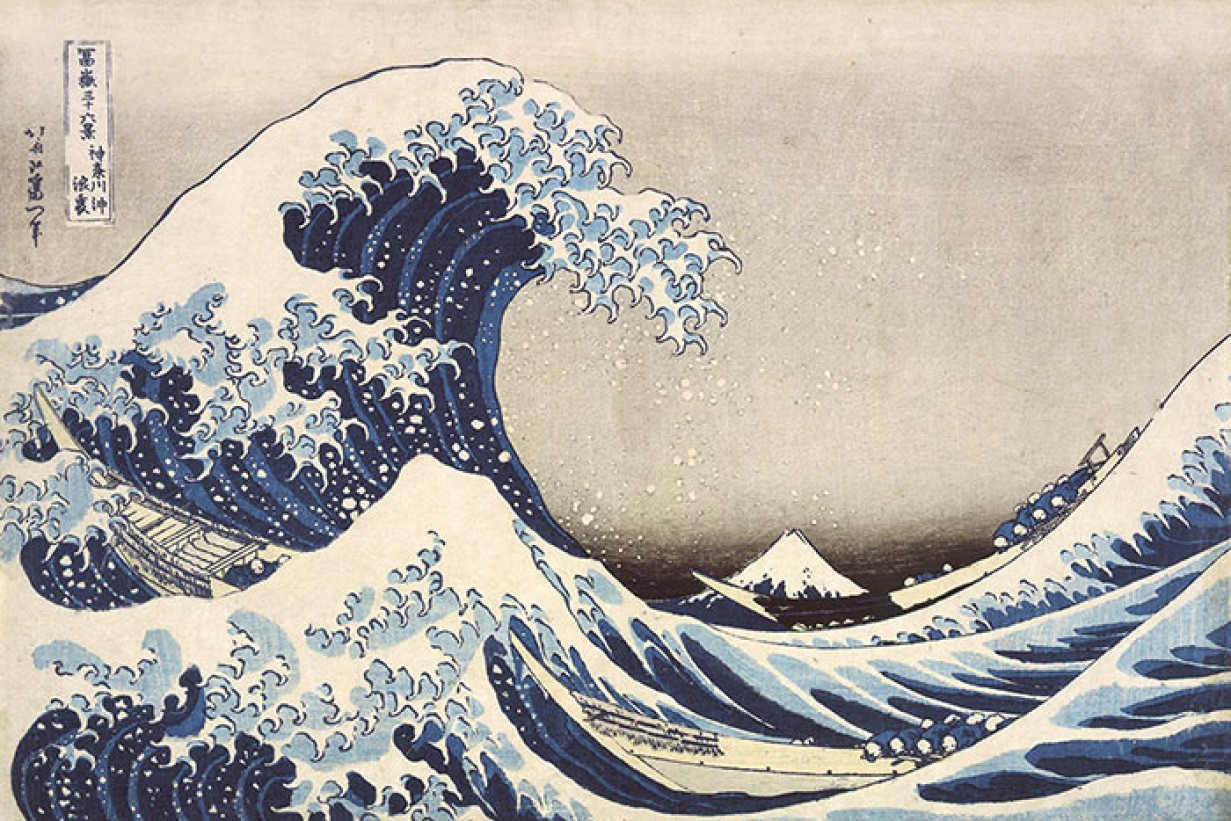

Japanese craftsmanship was unsurpassed mainly in the areas of swordsmithery, lacquerwork and color woodblock prints. The reinstallation particularly highlights the period from the 16th to the 20th century; Imari and Kakiemon porcelain wares produced in the 17th and 18th centuries were of great significance for the young European porcelain manufactories in Meißen and Vienna. Kakiemon decorations were much in demand at European aristocratic courts and soon were imitated on European-made porcelain.

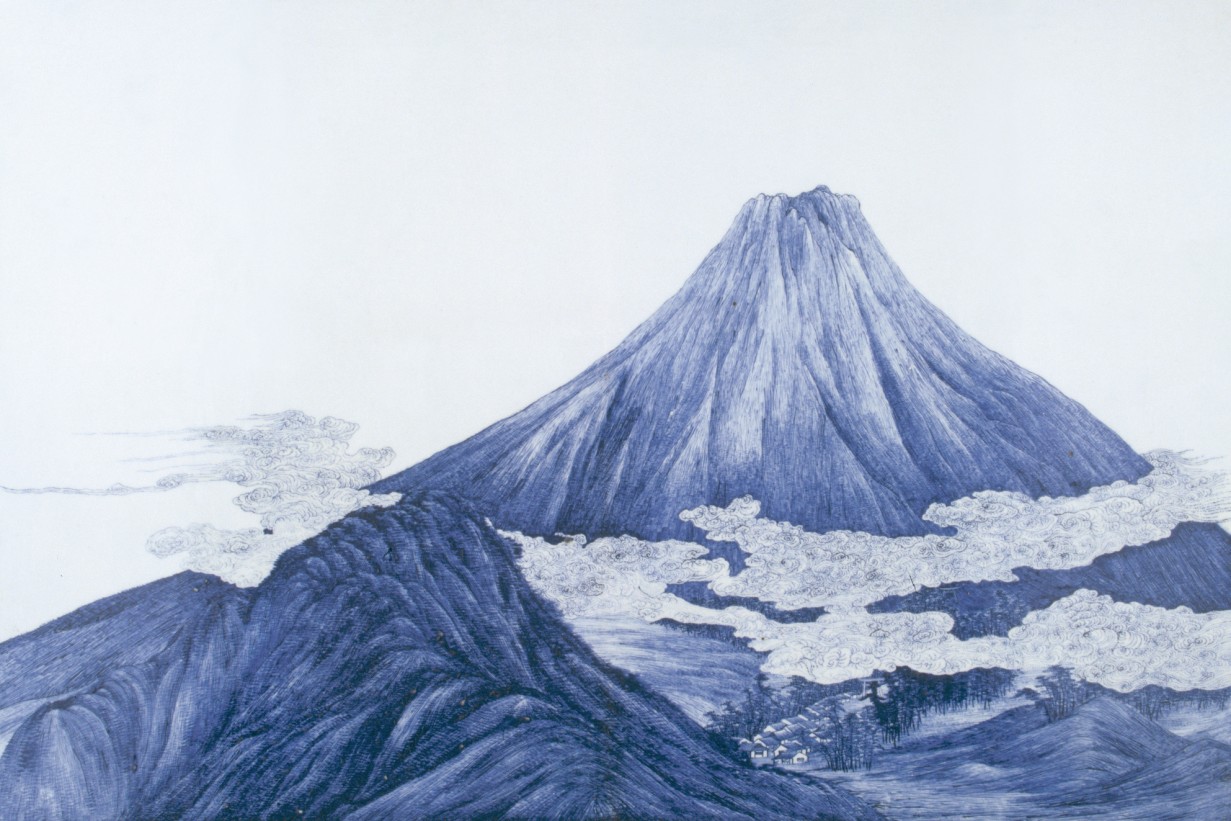

However, Japanese arts and crafts gained particular significance for the development of European art in the second half of the 19th. At the Vienna World’s Fair of 1873, Japan presented itself in grand style. Due to their high quality and complete documentation, the objects purchased after the end of the exposition or, for a major part, donated to the museum by the Japanese government are considered as reference items worldwide. A decorative plate by Kawamoto Masukichi I (1831–1907) showing Mount Fuji and a fanshaped wall decoration by Ikeda Taishin (1829–1903) illustrate the traditional artisanship practiced in Japanese manufactories and their collaboration with the best artists of the country.

The concluding objects of the Permanent Collection Asia testify European interest in East Asian Art. Around the turn of the century, European and Japanese artists were pretty similar in their attitudes, as is evidenced by the juxtaposition of a Japanese bronze vase—purchased at the 1902 Glasgow International Exhibition—and a ceramic piece by Alexandre Bigot (1862–1927), bought from the “Salon de l’Art Nouveau” in Paris. With his “Salon de l’Art Nouveau”, the art dealer Siegfried Bing (1838–1905) was not only a promulgator of Japanese arts and crafts, but also initiated many exhibitions and publications and inspired and encouraged artists all over Europe to study, and learn from, Asian art.

Curator Johannes Wieninger, Curator, MAK Asia Collection

Assistance Andrea Pospichal, Sabine Petraschek

Making centuries of cultural transfer between Asia and Europe traceable through a line-up of exemplary exhibits from the MAK collection is the goal that informs the reinstallation of the MAK Permanent Collection Asia. Since 2007, the exhibition room has been used for temporary shows about individual aspects of the comprehensive collection. Opening on 26 October 2012, the new presentation again provides a survey of the total range of the MAK’s fascinating Asian collection, which—comprised of holdings of 25,000 objects from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Iran, and Turkey dating from the Neolithic period up to the present day—ranks as one of the most comprehensive collections of Asian art in Europe.

Chinese porcelain, Japanese lacquerwork, Japanese colored woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) and Japanese dyeing stencils (katagami) make up the core of the MAK Asia Collection, which—like all comparable collections—in itself constitutes an instance of Orientalism: after all, the objects assembled here were all collected by Europeans and thus are representative of distinctly European tastes. Divided into forty small chapters, the reinstallation invites visitors on a time travel through Asian art history, which puts the “masterpieces” on exhibit in an art-and-cultural-history perspective.

Archaeological objects from China and Vietnam, particularly grave figures from the Han (206–220 AD) and Tang periods (618–907 AD), which already evidence contacts with Iranian art, mark the beginning of the reinstalled exhibition. Religious objects, sculptures, but also paintings indicate a paradigmatic transformation that went along with Buddhism, which emerged in the Tang period and eventually eclipsed the funeral cult. The richness of variations of Chinese and Japanese ceramics developed in an interaction with Western cultures and is demonstrated by examples from various epochs. Precious tea bowls and delicate ceramics document the arts-and crafts production of the early Song Dynasty (960–1279). From the time of the Mongolian rule in the Yuian Dynasty (1271- 1368), porcelain with cobalt-blue painting was much sought after by rulers’ courts throughout Asia, not least as a consequence of close contacts with the Islamic world. Like the early blue-and-white porcelains lacquer works oft that period show the Islamic horror vacui decoration.

It was only on the time of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) that the trade radius for Asian articles was extended to Europe. Royal and later also bourgeoisie households provided themselves with goods and wares from East Asia; Chinese porcelain became the utility tableware of a refined lifestyle. One unique example of this cultural blending that occurred from the 16th century is a tabletop from the library of Ambras Castle, Tyrol, which presumably was made by Chinese artisans in the South-Indian port city of Cochin (today: Kochi, Kerala) in a mixed Sino-European style on an order from Portuguese traders. Increasing demand for exported luxury products and East-Asian fashion influences on Europe informed the term “chinoiserie.” However, this well-known phenomenon in fact meant a reciprocal exchange: for European culture also was received with enthusiasm in China; Western artists and scientists were again and again invited to stay and work at the Imperial court in Beijing. Traditional Chinese art of the 18th century is documented in the exhibition by a unique vase, cut in Chinese style from a single block of jade (nephrite), whereas a silver and enamel globe is the central exhibit that stands for European influenced pieces.

Japanese craftsmanship was unsurpassed mainly in the areas of swordsmithery, lacquerwork and color woodblock prints. The reinstallation particularly highlights the period from the 16th to the 20th century; Imari and Kakiemon porcelain wares produced in the 17th and 18th centuries were of great significance for the young European porcelain manufactories in Meißen and Vienna. Kakiemon decorations were much in demand at European aristocratic courts and soon were imitated on European-made porcelain.

However, Japanese arts and crafts gained particular significance for the development of European art in the second half of the 19th. At the Vienna World’s Fair of 1873, Japan presented itself in grand style. Due to their high quality and complete documentation, the objects purchased after the end of the exposition or, for a major part, donated to the museum by the Japanese government are considered as reference items worldwide. A decorative plate by Kawamoto Masukichi I (1831–1907) showing Mount Fuji and a fanshaped wall decoration by Ikeda Taishin (1829–1903) illustrate the traditional artisanship practiced in Japanese manufactories and their collaboration with the best artists of the country.

The concluding objects of the Permanent Collection Asia testify European interest in East Asian Art. Around the turn of the century, European and Japanese artists were pretty similar in their attitudes, as is evidenced by the juxtaposition of a Japanese bronze vase—purchased at the 1902 Glasgow International Exhibition—and a ceramic piece by Alexandre Bigot (1862–1927), bought from the “Salon de l’Art Nouveau” in Paris. With his “Salon de l’Art Nouveau”, the art dealer Siegfried Bing (1838–1905) was not only a promulgator of Japanese arts and crafts, but also initiated many exhibitions and publications and inspired and encouraged artists all over Europe to study, and learn from, Asian art.

Curator Johannes Wieninger, Curator, MAK Asia Collection

Assistance Andrea Pospichal, Sabine Petraschek