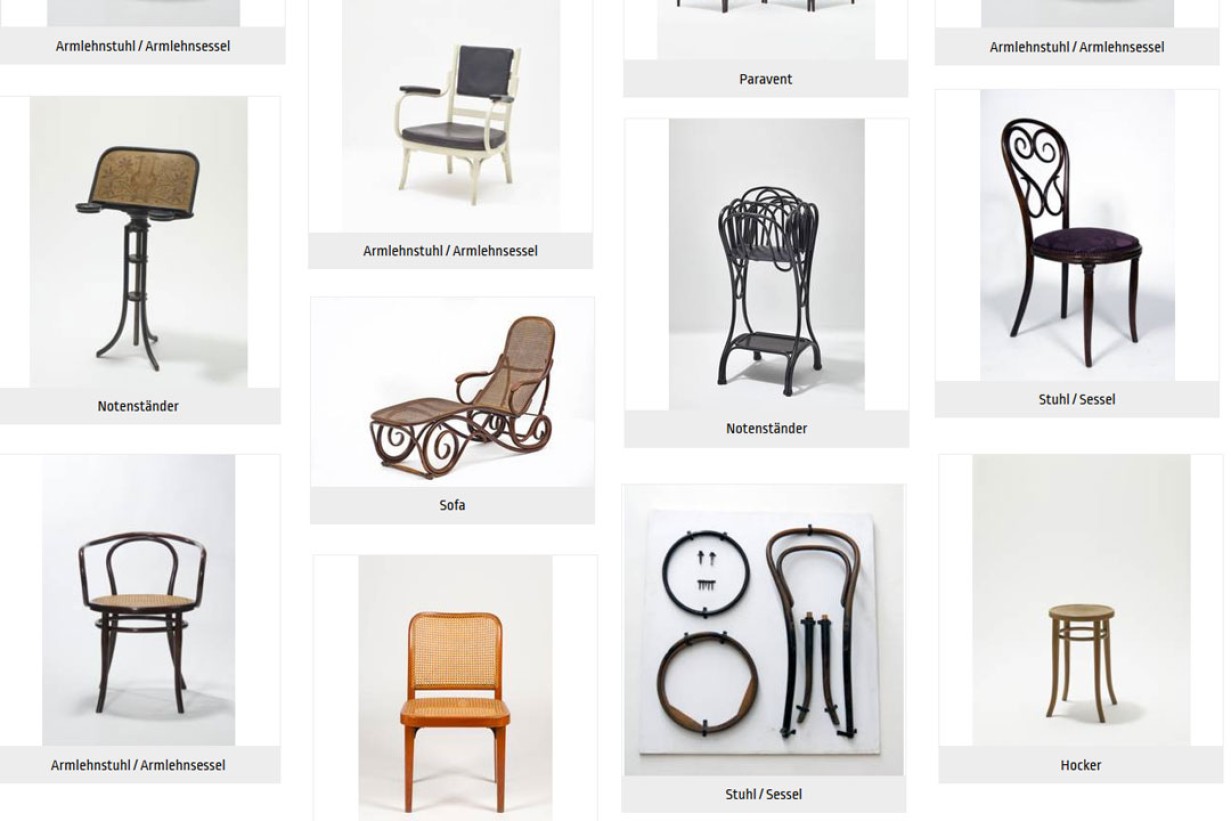

Study Collection Seating Furniture

Curator: Sebastian Hackenschmidt

Previous Image

Study Collection Seating Furniture 1993-2013

Part of our material memory is located in this room. Is it only a collection of arbitrarily selected household items or is it indeed history manifesting itself here as the totality of our awareness? To what extent do we still relate to these objects in a direct way? Or has an archive accumulated here of has-beens, whose lowest common denominator comprises the classifications “museum quality” or “second-hand”? We have the choice between these two associations: between the character of an artefact either as an object or as a function. The latter allows the museum piece to reinstate itself once again as a component of our day-to-day consumer society context. Instead of a one-dimensional history of style we experience a three-dimensional pedigree of our own cultural history. In the process, the self-evident receives the chance of becoming evident again.

This is brought about by means of visually sensuous and non-didactic communication. The visible contrast of different or similar types, functions, stages of development, and materials succeeds in evoking an awareness of the multilayered experience involved in “seating” and, by addressing the viewer directly, elicits an evaluative reaction that may well lead to a reappraisal of our attitude to seating and how it is so often taken for granted. This stimulation may well contribute to transforming an undiscriminating consumer into a mature and responsible one by arousing in him considerations that have been obliterated by the avalanche of everyday products.

The chair is the piece of furniture closest to the human being. Its proportions are most intimately related to the human body. From the changing aesthetics and functionality of the seat the social morphology of body language can be interpreted. This seems to find expression between the two opposite poles of prestige and comfort, which emerge according to the respective defined values and set priorities. A high, straight backed armchair demands different clothing and posture from the sitter than one with a low, backward-sloping, rounded backrest.

The question of principle arises as to whether furniture should conform to the human body in the sitting position, or vice versa. An extreme example of the latter is the “Sacco” or “Bean Bag,” on show here, a typical model of seating furniture for the '68 generation. The concept of the suite of seat furniture, which did not arise until the 18th century, entails a number of matching seating furniture types combined to form a decorative whole. It expresses the fact that there is no longer any need to differentiate between the status of the individual users. This development could only assert itself at a time when courtly precedent stipulated a less strict hierarchy between the individual types of seating. In our subconscious, however, this historical development lives on today. As late as 1922, the “Handbook of Good Breeding and Fine Manners” ordained: “As a lady your proper place is on the sofa, to the right of the lady of the house. As a young girl you should make use of a chair.” Seating furniture unifies the language of forms and of the body into a legible, cultural-historical whole ... / Christian Witt-Dörring, curator of the Furniture and Woodwork Collection at the time when the MAK Study Collection’s seating furniture presentation was reconceived.

Part of our material memory is located in this room. Is it only a collection of arbitrarily selected household items or is it indeed history manifesting itself here as the totality of our awareness? To what extent do we still relate to these objects in a direct way? Or has an archive accumulated here of has-beens, whose lowest common denominator comprises the classifications “museum quality” or “second-hand”? We have the choice between these two associations: between the character of an artefact either as an object or as a function. The latter allows the museum piece to reinstate itself once again as a component of our day-to-day consumer society context. Instead of a one-dimensional history of style we experience a three-dimensional pedigree of our own cultural history. In the process, the self-evident receives the chance of becoming evident again.

This is brought about by means of visually sensuous and non-didactic communication. The visible contrast of different or similar types, functions, stages of development, and materials succeeds in evoking an awareness of the multilayered experience involved in “seating” and, by addressing the viewer directly, elicits an evaluative reaction that may well lead to a reappraisal of our attitude to seating and how it is so often taken for granted. This stimulation may well contribute to transforming an undiscriminating consumer into a mature and responsible one by arousing in him considerations that have been obliterated by the avalanche of everyday products.

The chair is the piece of furniture closest to the human being. Its proportions are most intimately related to the human body. From the changing aesthetics and functionality of the seat the social morphology of body language can be interpreted. This seems to find expression between the two opposite poles of prestige and comfort, which emerge according to the respective defined values and set priorities. A high, straight backed armchair demands different clothing and posture from the sitter than one with a low, backward-sloping, rounded backrest.

The question of principle arises as to whether furniture should conform to the human body in the sitting position, or vice versa. An extreme example of the latter is the “Sacco” or “Bean Bag,” on show here, a typical model of seating furniture for the '68 generation. The concept of the suite of seat furniture, which did not arise until the 18th century, entails a number of matching seating furniture types combined to form a decorative whole. It expresses the fact that there is no longer any need to differentiate between the status of the individual users. This development could only assert itself at a time when courtly precedent stipulated a less strict hierarchy between the individual types of seating. In our subconscious, however, this historical development lives on today. As late as 1922, the “Handbook of Good Breeding and Fine Manners” ordained: “As a lady your proper place is on the sofa, to the right of the lady of the house. As a young girl you should make use of a chair.” Seating furniture unifies the language of forms and of the body into a legible, cultural-historical whole ... / Christian Witt-Dörring, curator of the Furniture and Woodwork Collection at the time when the MAK Study Collection’s seating furniture presentation was reconceived.

Media

Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill: Armchair from a Set of Bedroom and Dressing Room Furniture for August and Serena Lederer

Vienna, 1924

Otto Wagner: Daybed from the Director's Office of the Austrian Postsparkasse [Postal Savings Bank]

Vienna, 1906

![Otto Wagner: Daybed from the Director's Office of the Austrian Postsparkasse [Postal Savings Bank]](/jart/prj3/mak-resp/images/cache/acfae14244d6e8923030d58262264444/0x811481EAA6BD6A7702B3B5852045F369.jpeg)