Permanent Collection Baroque Rococo Classicism

Artistic intervention: Donald Judd

© MAK

© MAK

© MAK

Previous Image

I was doubtful about the idea of artists making installations of earlier objects; I am still doubtful. I think installation should be the responsibility of the curators of the objects, although I continue to be critical of the generally artificial way in which objects are installed. To have artists make such installations is likely to perpetuate devious installation. I accepted the problem as a favour to the museum, and I accepted as a premise for myself that I would not contradict the judgement of the curator responsible, Christian Witt-Dörring. I think we did our best. The museum's premise, the installation's set fact, was that the Dubsky room, originally a room in a palace, had to be reconstructed in a much larger room of the museum. I was told there was no alternative. The room could be remade either in one of the corners of the exhibition room, leaving an awkward right angle for the other furniture, or it could be remade in the center of the room, leaving a symmetrical space and possibly establishing a room within a room - a good idea. I asked that this be done. The Dubsky room is too large and is awkward, but placing it in the center was the right decision. The room and most of the other furniture were made in the eighteenth century for the aristocracy. The room's grandeur is uncertain, and therefore excessive. It is uneasy; Chardin is not uneasy. All architecture and most installations are now uneasy. Why is Chardin simple, strong and easy? The separate pieces of furniture are placed symmetrically, usually in pairs, usually opposite each other. A rectangular space usually determines this. The positioning of the furniture was also carefully decided with regard to the size, color, and type of each piece. I asked for part of the moulding under the ceiling of the large room to be repeated around the exterior of the Dubsky room, to further incorporate it into the eighteenth century space made in the nineteenth century, and to reduce the excessive generality of its exterior. This is a small, uneasy room uneasily placed in a large, doubly uneasy room. I think it should be in the basement. But Witt-Dörring and I did our best, uneasily./ Donald Judd

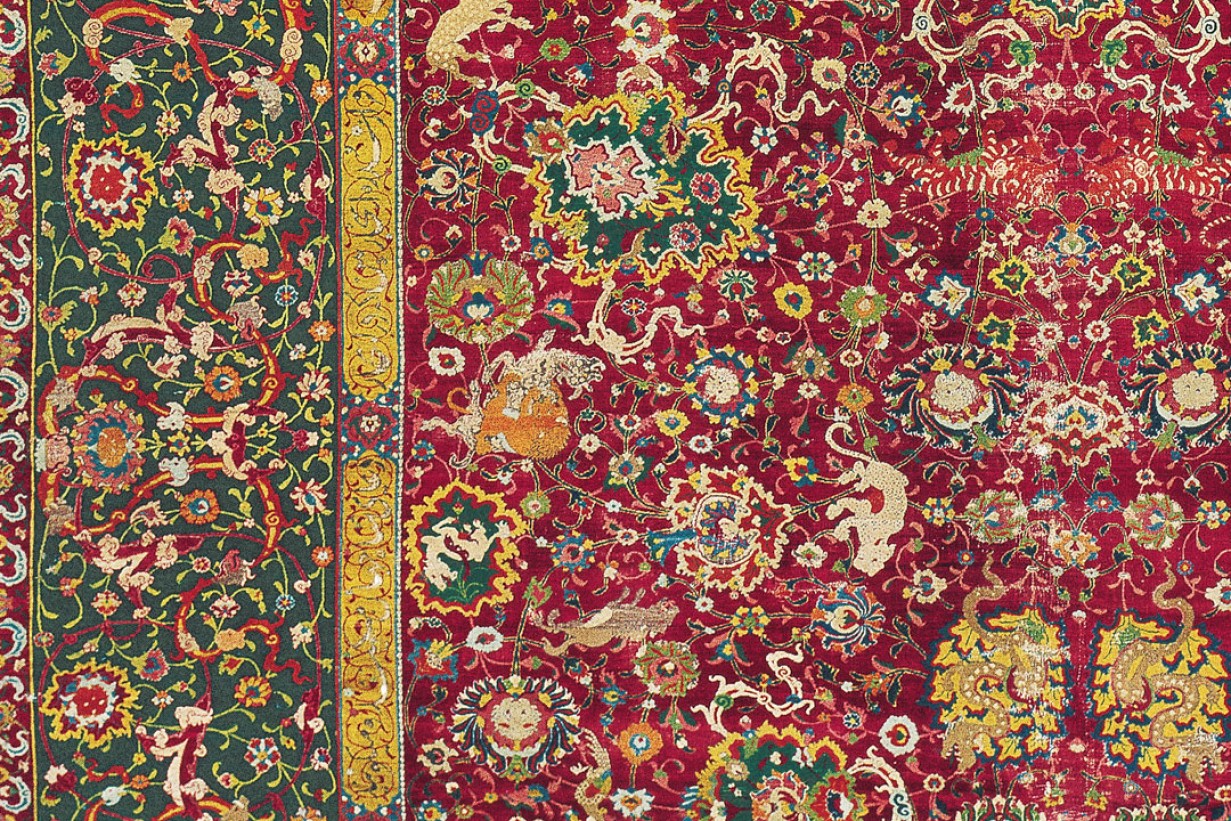

The MAK's collections contain some splendid examples of eighteenth-century cabinet-making. The emphasis in the collection is on pieces from the cultural realm encompassing Austria, France, and Germany. These bear witness to the tremendous typological, technical, and formal developments that took place during the course of the eighteenth century. The bureau cabinet, with its origins in the seventeenth century, is gradually replaced as a prestigious furniture item by the writing desk, the southern German form of which is known as a "tabernacle cabinet.” In France, the chest of drawers develops as a new kind of case furniture providing storage space in the living area, a reaction to the growth of the private sphere and the increasing desire for comfort. Forms of writing furniture that arise include the basic desk and the cylinder desk. The surface decoration of furniture becomes more varied, and is used to meet novel requirements and fashions (wooden and Boulle marquetry, lacquer, porcelain, etc.). Interior design itself becomes more uniform with the development of mobile and immobile furnishings. Furniture enters into decorative unity, and often structural unity, with the room. The porcelain room from the Dubsky Palace in Brno eloquently documents this, as well as marking the beginning of porcelain production in Vienna, from 1719 onward. / Christian Witt-Dörring - curator of the MAK Furniture and Woodwork Collection during the phase of the reinstallation of the MAK Permanent Collection in the early 1990s)

The MAK's collections contain some splendid examples of eighteenth-century cabinet-making. The emphasis in the collection is on pieces from the cultural realm encompassing Austria, France, and Germany. These bear witness to the tremendous typological, technical, and formal developments that took place during the course of the eighteenth century. The bureau cabinet, with its origins in the seventeenth century, is gradually replaced as a prestigious furniture item by the writing desk, the southern German form of which is known as a "tabernacle cabinet.” In France, the chest of drawers develops as a new kind of case furniture providing storage space in the living area, a reaction to the growth of the private sphere and the increasing desire for comfort. Forms of writing furniture that arise include the basic desk and the cylinder desk. The surface decoration of furniture becomes more varied, and is used to meet novel requirements and fashions (wooden and Boulle marquetry, lacquer, porcelain, etc.). Interior design itself becomes more uniform with the development of mobile and immobile furnishings. Furniture enters into decorative unity, and often structural unity, with the room. The porcelain room from the Dubsky Palace in Brno eloquently documents this, as well as marking the beginning of porcelain production in Vienna, from 1719 onward. / Christian Witt-Dörring - curator of the MAK Furniture and Woodwork Collection during the phase of the reinstallation of the MAK Permanent Collection in the early 1990s)

Media

Nikolaus Haberstumpf, Cabinet, Eger, Böhmen (Cheb, Tschechische Republik), 1723, H 1760 / 1941 © MAK

![Central group of the centerpiece from Zwettl Monastery, Ke 6823 / 1926 The Production of Porcelain [Die Porzellanerzeugung]](/jart/prj3/mak-resp/images/cache/0845326e82ca9e18c1d29152b94e4fe4/0xFFD96636D476E67F95B95D842EDAEE5D.jpeg)