Previous Image

17.9.1996—30.9.1996

MAK Center Los Angeles, Schindler House

The residents joined with local colleagues to present an evening of festivities for the Final Projects exhibition entitled "Multi-Media Celebration." In the tradition of "happenings," this art event encompassed a range of simultaneous activities. In Gilbert Bretterbauer's house, poet Benjamin Weissman read from his work and artist Christiana Glidden created a light sculpture. Videos, slides and Super-8 films were continuously projected on screens hung from the roof of the Schindler House. Andrea Lenardin and food stylist Alison Attenborough created a buffet and music was provided by DJs Marnie Castor and Josh Berman.

For Final Projects, Gilbert Bretterbauer constructed "The House" on the front lawn of the Schindler House by using bamboo harvested on the grounds and interpreting Schindler design concepts. "The House" utilized the interlocking "L" structure of the Schindler House and engaged Schindler's interpenetration of indoor and outdoor spaces through the use of translucent fabrics and lighting. Late in his life, Schindler spoke of "removing architecture." Bretterbauer's nomadic house -- the structure can be moved and reconstructed in an hour -- with its fabric walls was a contemporary expression of that ideal. Just as Schindler's house provided a canvas for the artists of Final Projects, Bretterbauer's house played host to the work of other artists. In two of the three rooms, the work of Los Angeles artists Liz Larner and Thomas Baldwin were presented for the duration of the exhibition.

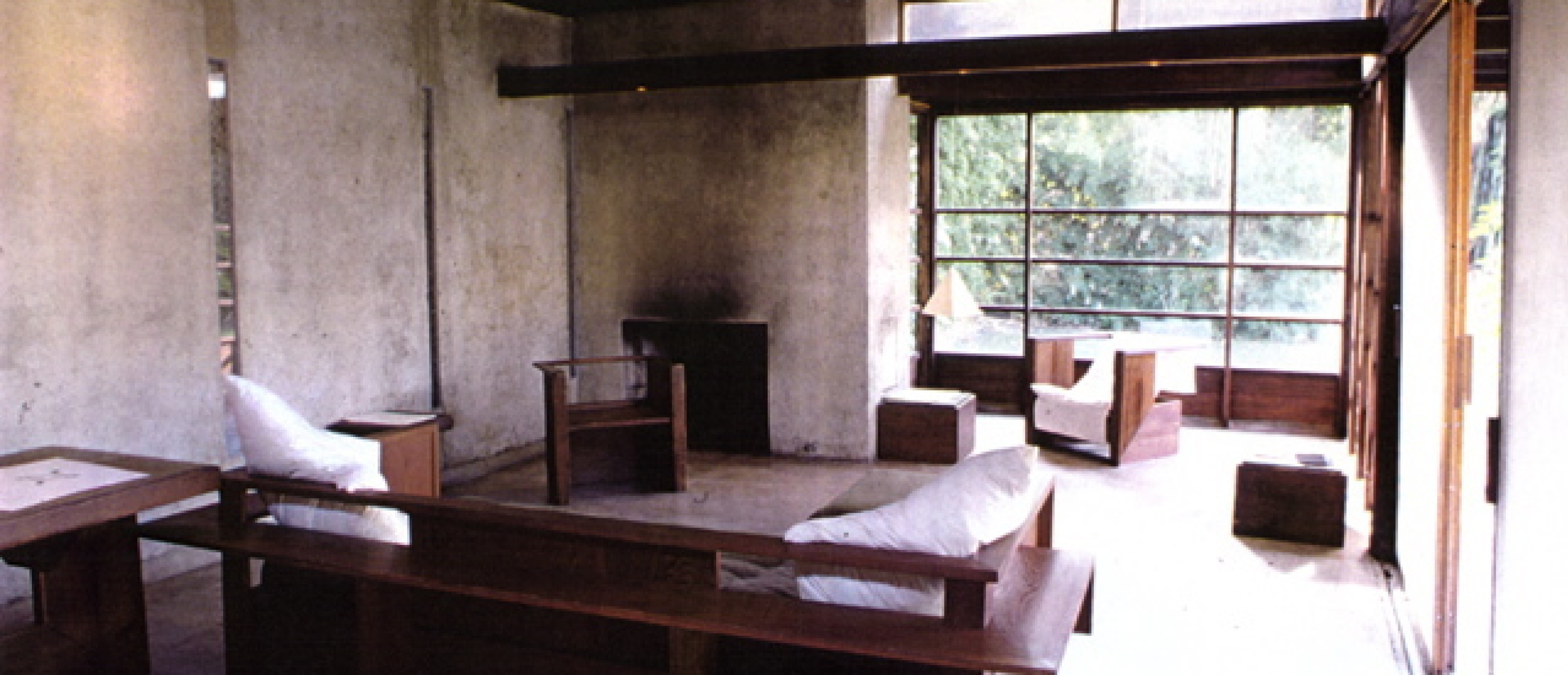

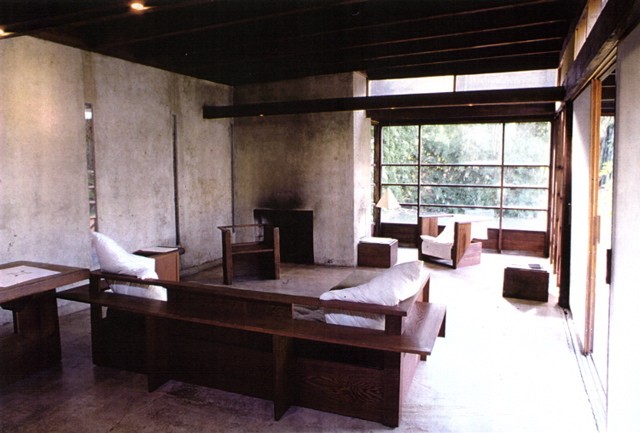

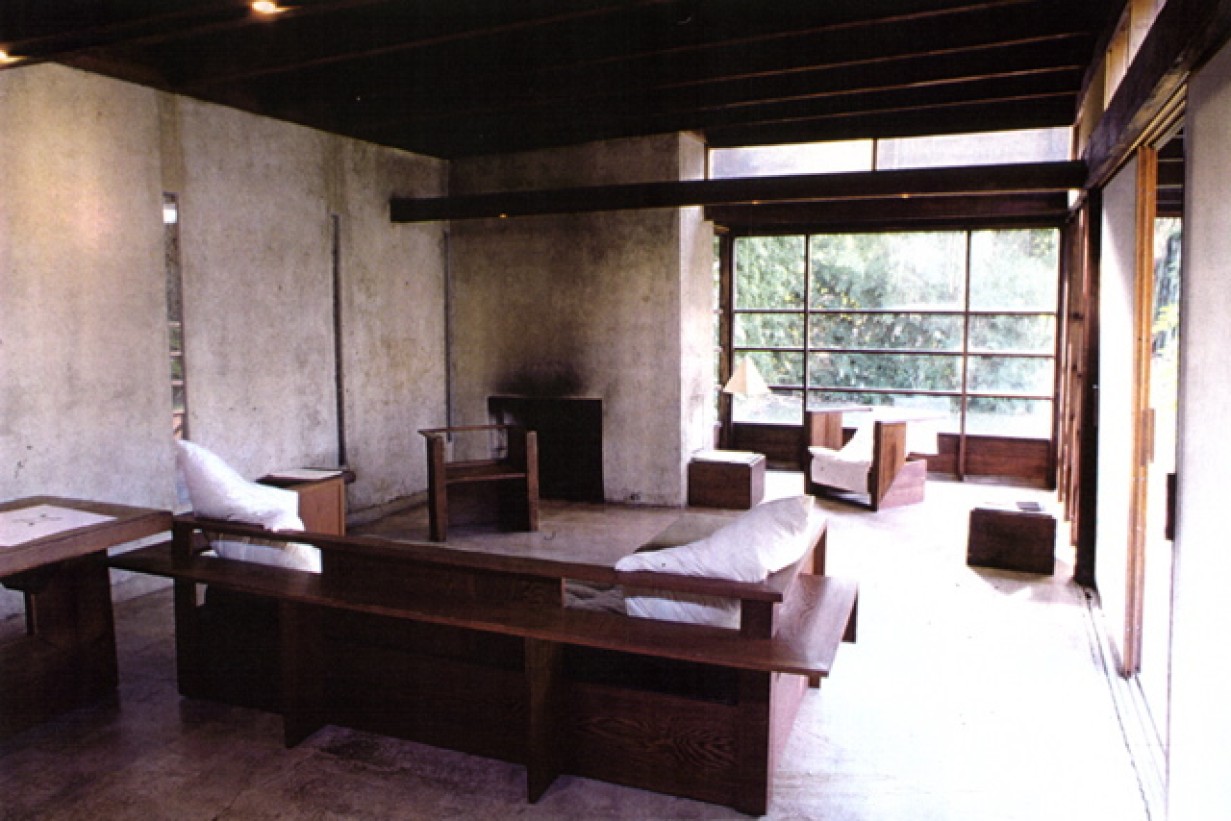

Architect Marta Fuetterer interacted with Schindler's architecture by covering the original Schindler-designed furniture in the architect's studio with sheets, creating a newly-modulated space with Schindler's own means. In her piece, "The Golden Absence," she also inflected the space with light, rebuilding lamps to Schindler's original design. Covered furniture evoked a variety of associations -- the impulse to cleanliness, the departure of inhabitants, and temporary displacement for painting or remodeling. Fuetterer drew attention to the emotional resonance of the space with her subtle interventions.

Christoph Kasperkovitz described his work "God is a Butcher" as a "video-sculpture." This finely-crafted piece presented a contemporary interpretation of late medieval representations of the "dance of death," which were meditations on mortality. Here, three child mannequins were given horns which were reconstructed to represent different attitudes toward the inevitability of death: innocence, carpe diem ("live for today"), indifference, and religious ecstasy. The middle figure, which found religion, bore a video monitor in its head that screened a variety of American tele-evangelist preachers. Upon coming to the U.S., Kasperkovitz was fascinated by this salesman-like approach to spirituality.

Inside the Schindler House, Andrea Lenardin displayed "Instant Days." This highly-machined "Rolodex" supplied nourishment for the emotions and was an extension of her ongoing project entitled "The Museum of Consumption." A motorized axle slowly turned the Rolodex cards that consisted of vacuum packed polaroid images and objects. The nutritional content of each packet was described in the language of human emotions. Like instant meals, each packet depicted a hypothetical day and evoked a multiplicity of responses in viewers. Inspired by American consumerism, Lenardin's work commented on our propensity to make choices without thinking, similar to the practice of selecting a frozen meal at the grocery store.

For Final Projects, Gilbert Bretterbauer constructed "The House" on the front lawn of the Schindler House by using bamboo harvested on the grounds and interpreting Schindler design concepts. "The House" utilized the interlocking "L" structure of the Schindler House and engaged Schindler's interpenetration of indoor and outdoor spaces through the use of translucent fabrics and lighting. Late in his life, Schindler spoke of "removing architecture." Bretterbauer's nomadic house -- the structure can be moved and reconstructed in an hour -- with its fabric walls was a contemporary expression of that ideal. Just as Schindler's house provided a canvas for the artists of Final Projects, Bretterbauer's house played host to the work of other artists. In two of the three rooms, the work of Los Angeles artists Liz Larner and Thomas Baldwin were presented for the duration of the exhibition.

Architect Marta Fuetterer interacted with Schindler's architecture by covering the original Schindler-designed furniture in the architect's studio with sheets, creating a newly-modulated space with Schindler's own means. In her piece, "The Golden Absence," she also inflected the space with light, rebuilding lamps to Schindler's original design. Covered furniture evoked a variety of associations -- the impulse to cleanliness, the departure of inhabitants, and temporary displacement for painting or remodeling. Fuetterer drew attention to the emotional resonance of the space with her subtle interventions.

Christoph Kasperkovitz described his work "God is a Butcher" as a "video-sculpture." This finely-crafted piece presented a contemporary interpretation of late medieval representations of the "dance of death," which were meditations on mortality. Here, three child mannequins were given horns which were reconstructed to represent different attitudes toward the inevitability of death: innocence, carpe diem ("live for today"), indifference, and religious ecstasy. The middle figure, which found religion, bore a video monitor in its head that screened a variety of American tele-evangelist preachers. Upon coming to the U.S., Kasperkovitz was fascinated by this salesman-like approach to spirituality.

Inside the Schindler House, Andrea Lenardin displayed "Instant Days." This highly-machined "Rolodex" supplied nourishment for the emotions and was an extension of her ongoing project entitled "The Museum of Consumption." A motorized axle slowly turned the Rolodex cards that consisted of vacuum packed polaroid images and objects. The nutritional content of each packet was described in the language of human emotions. Like instant meals, each packet depicted a hypothetical day and evoked a multiplicity of responses in viewers. Inspired by American consumerism, Lenardin's work commented on our propensity to make choices without thinking, similar to the practice of selecting a frozen meal at the grocery store.

Previous Image