Vorheriges Bild

19.3.1999—21.3.1999

Mackey Apartments

Swedish artists Åse Frid and Johan Frid were highly influenced by the stories of Swedish children's book author Astrid Lindgren when they began work on issues in which the "real imagination" and the saga got stuck in a "point of no return" in the fast-paced urban life. During their stay in Los Angeles, however, the constant feeling of "luxury, anxiety, and sexual nervousness," as they lived together in a Schindler-designed house, altered their views. They based their installation on a "fine, old-fashioned motto" hidden in obscurity as a result of "shrinkage of the room." But traces of the motto showed in their work in both their efforts to "integrate everything" under "forms of organized freedom" and in how they dealt internally with the problems or questions brought forth by this motto.

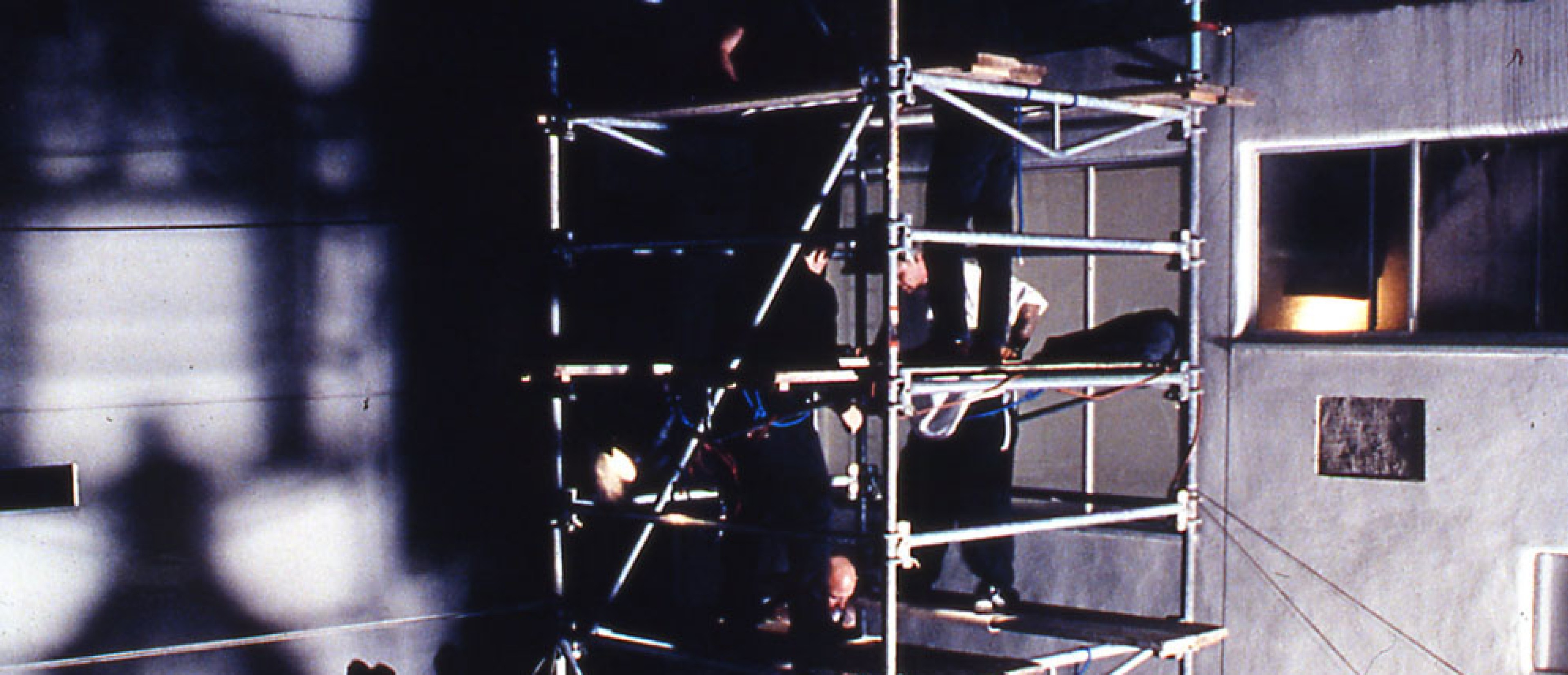

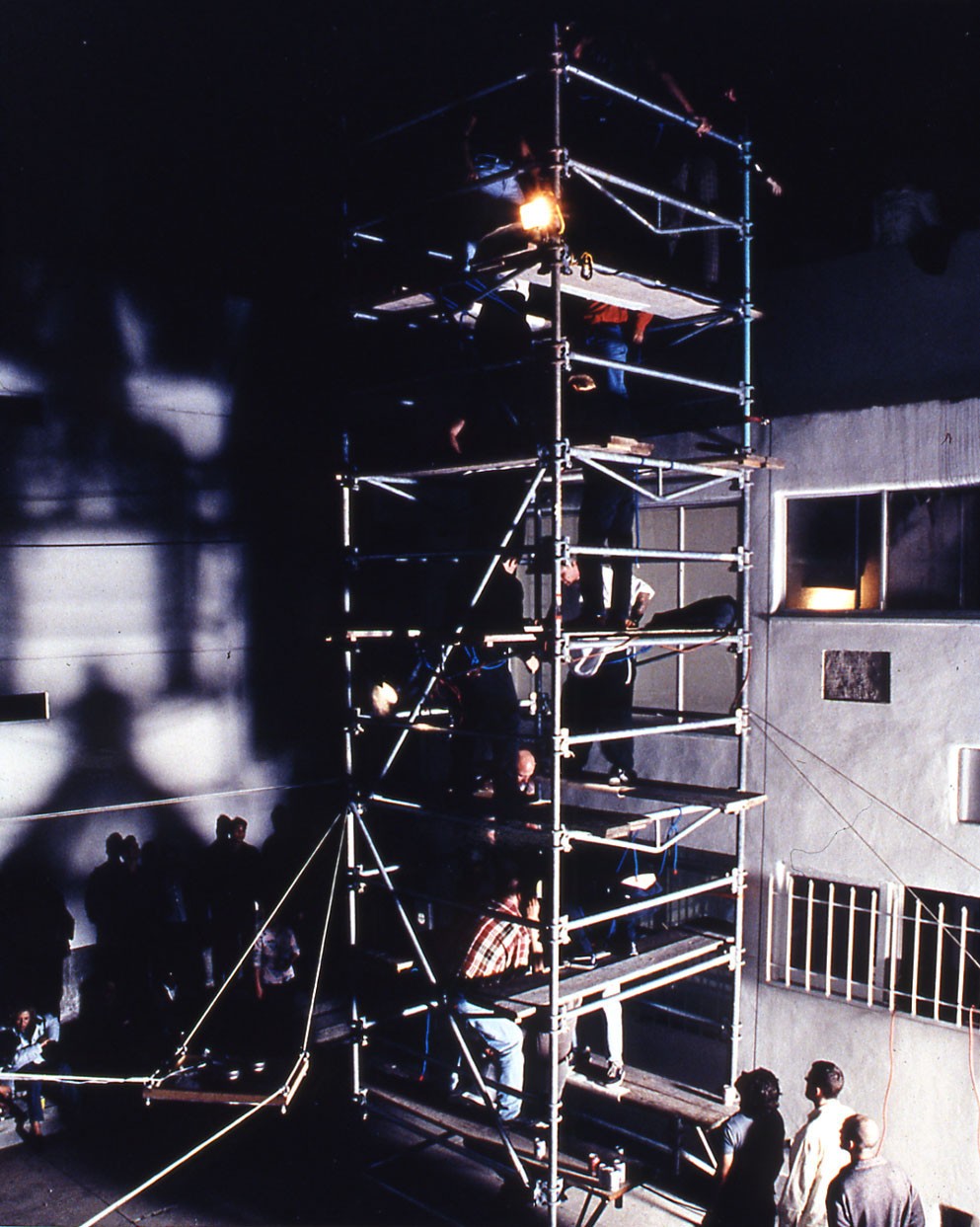

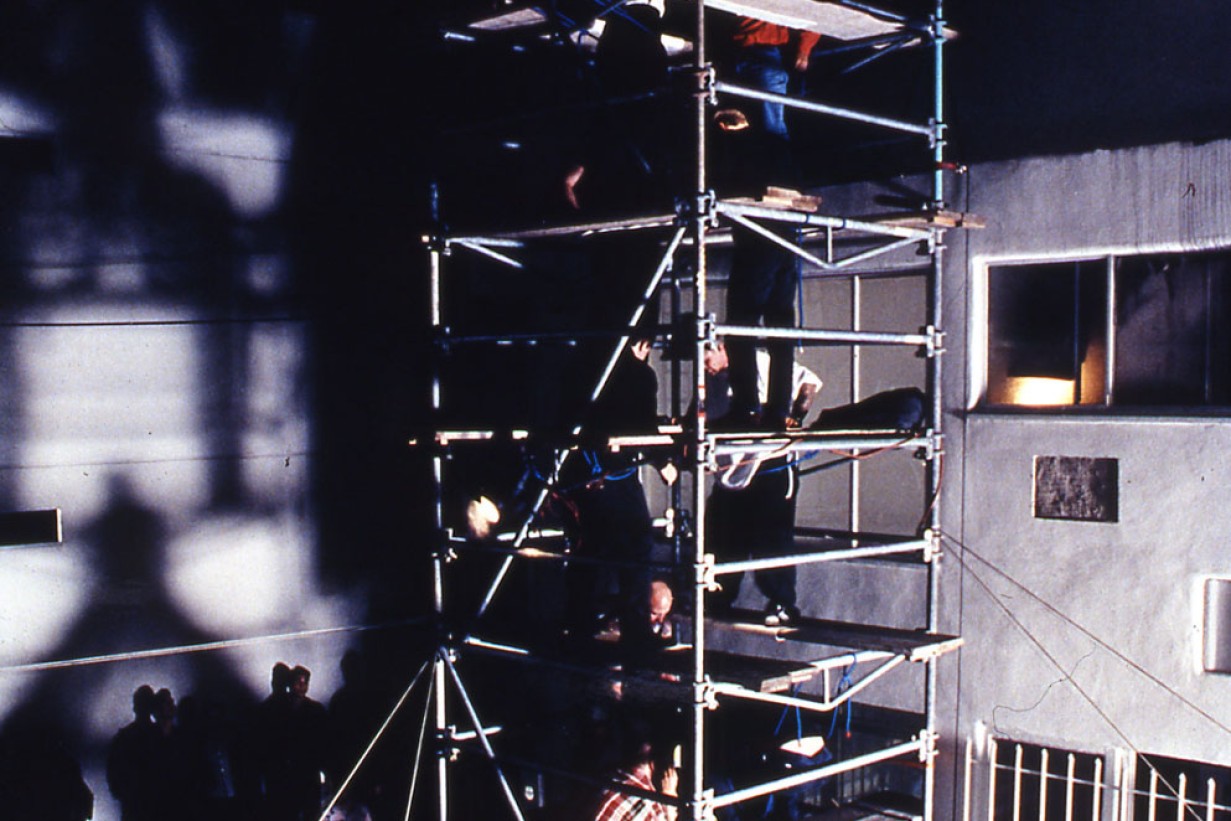

Ali Janka and Tobias Urban, two members of the Austrian artists collaborative team "Gelatin" (now "Gelitin") introduced a new project, "The Human Elevator." In this work, Gelatin actively pursued environments conducive to "response and activation within a given space by turning it over to sensual experience, intensity, surprise, and delight." They created interactive situations which invited visitor participation by appealing to a playful sense of fun. In the summer 1998 at New York's P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, viewers could engage in a variety of games and sensual experiences provided by Gelatin in the outdoor sculpture garden, including a "sauna" and "refrigeration room."

Exploiting L.A.'s beach-and-body culture, Gelatin's human elevator utilized the physical strength of body builders who, positioned on scaffolding, hoisted participants to the roof of the Mackey Apartments.

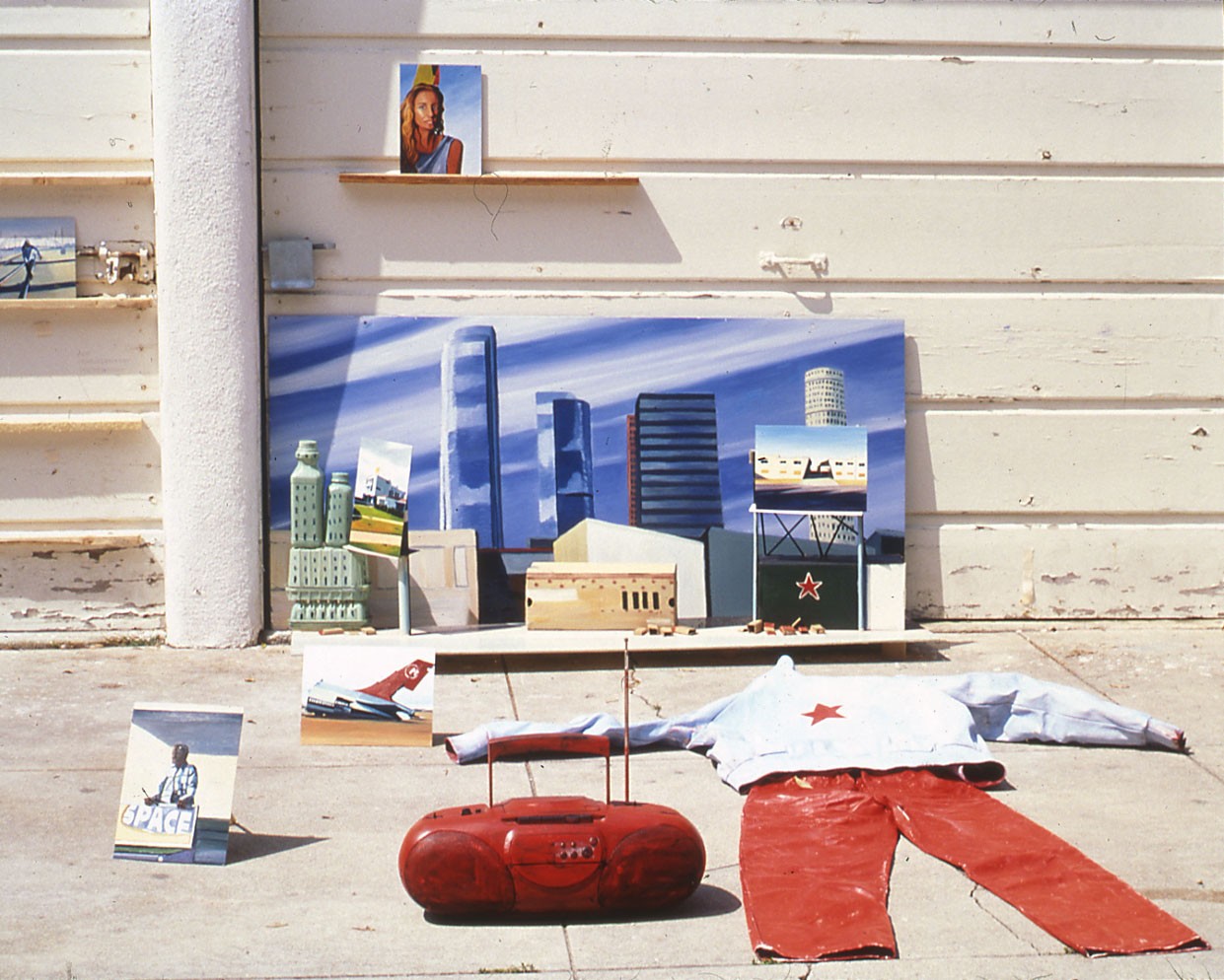

Austrian artist Anna Meyer considered Los Angeles as a 1:1 model, a city both real and simulated. She interpreted her observations and experiences through models and large scale paintings. Meyer's realistic paintings used photography as a reference point. The subject matter of the photos—the city, people, bars, sexuality, homelessness, social structures, etc.—provided a context that was interpreted through painting. Meyer considered her models, made from everyday materials and painted, as "3-D pictures." She saw Los Angeles, with its many billboards, painted facades, wall murals, and bus-stop placards, as a "big picture carrier" and the experience of traveling through the city by car as similar to being in a movie.

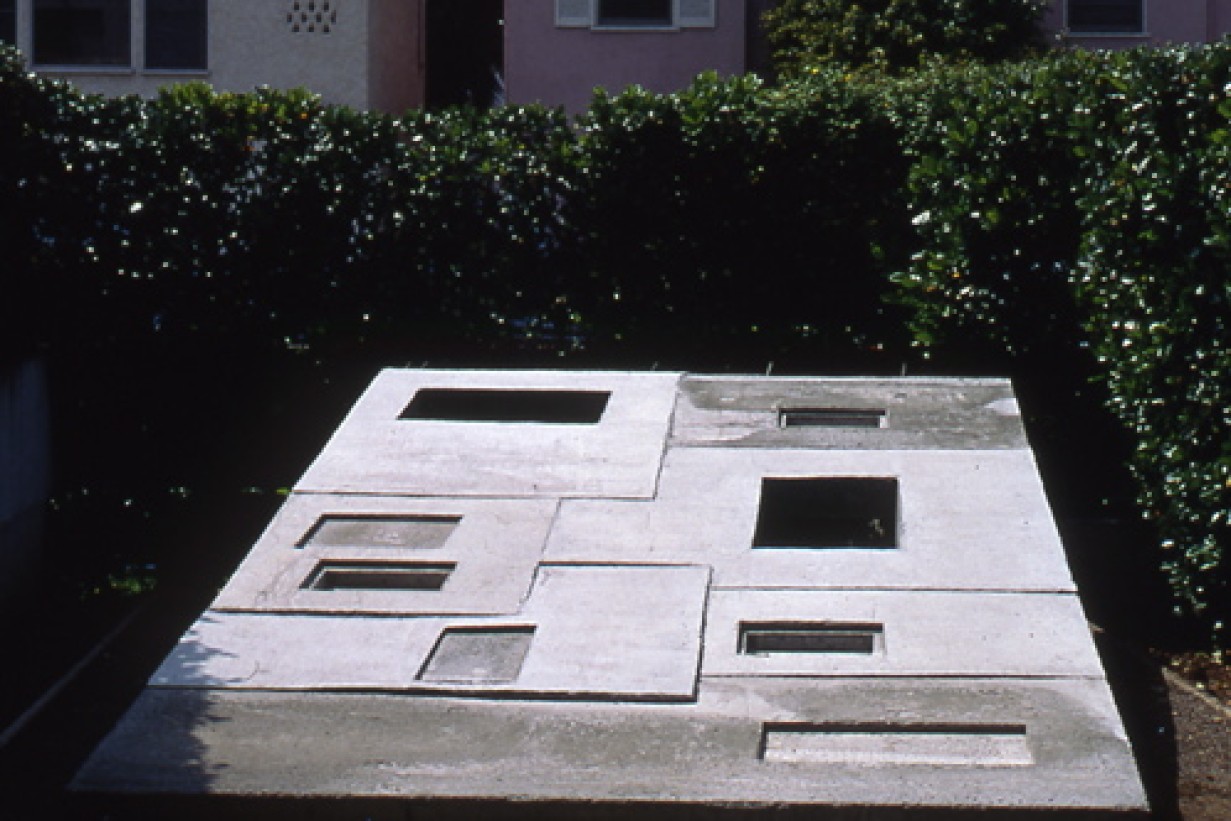

Density and its consequences for urbanity were the focus of Raw 'n Cooked, the partnership of Austrian architects Walter Kraeutler and Carl Schlaeffer. They noted that parking lots could be seen as symbolic of Los Angeles' economic and urban densities, occupying vast horizontal spaces in the suburbs and tight, multi-story structures in Downtown. Cemeteries, too, embody much of L.A.'s civic structures, organized into grids demarcating different "neighborhoods" and densities. In the exhibition, Raw 'n Cooked built a sculpture, a "construction of memories, using the language of an urban city with its vertical layers, its transportation system and its inhabitants."

Ali Janka and Tobias Urban, two members of the Austrian artists collaborative team "Gelatin" (now "Gelitin") introduced a new project, "The Human Elevator." In this work, Gelatin actively pursued environments conducive to "response and activation within a given space by turning it over to sensual experience, intensity, surprise, and delight." They created interactive situations which invited visitor participation by appealing to a playful sense of fun. In the summer 1998 at New York's P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, viewers could engage in a variety of games and sensual experiences provided by Gelatin in the outdoor sculpture garden, including a "sauna" and "refrigeration room."

Exploiting L.A.'s beach-and-body culture, Gelatin's human elevator utilized the physical strength of body builders who, positioned on scaffolding, hoisted participants to the roof of the Mackey Apartments.

Austrian artist Anna Meyer considered Los Angeles as a 1:1 model, a city both real and simulated. She interpreted her observations and experiences through models and large scale paintings. Meyer's realistic paintings used photography as a reference point. The subject matter of the photos—the city, people, bars, sexuality, homelessness, social structures, etc.—provided a context that was interpreted through painting. Meyer considered her models, made from everyday materials and painted, as "3-D pictures." She saw Los Angeles, with its many billboards, painted facades, wall murals, and bus-stop placards, as a "big picture carrier" and the experience of traveling through the city by car as similar to being in a movie.

Density and its consequences for urbanity were the focus of Raw 'n Cooked, the partnership of Austrian architects Walter Kraeutler and Carl Schlaeffer. They noted that parking lots could be seen as symbolic of Los Angeles' economic and urban densities, occupying vast horizontal spaces in the suburbs and tight, multi-story structures in Downtown. Cemeteries, too, embody much of L.A.'s civic structures, organized into grids demarcating different "neighborhoods" and densities. In the exhibition, Raw 'n Cooked built a sculpture, a "construction of memories, using the language of an urban city with its vertical layers, its transportation system and its inhabitants."

Vorheriges Bild