"Sitzen 69" revisited

Austrian Chair Design in the 1960s. Sebastian Hackenschmidt, curator, MAK Collection of Furniture and Woodwork

Previous Image

Like hardly any other 20th-century decade, the 1960s stand for innovative furniture design. Thinking back to the seating furniture of that period, we can easily make out several examples that are undeniably modern classics: the famous Panton Chair, prominent among design icons as the first cantilever chair made out of plastic; the legendary Sacco by Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini and Franco Teodoro, a playfully revolutionary seating object from 1968 that captured the spirit of its era; the inflatable plastic chair Blow, likewise created under the influence of the Italian Anti-Design movement; and perhaps also the futuristic Djinn seats by Oliver Morgue, used by Stanley Kubrick in his science fiction movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. Such designs constituted a certain affront to the postwar period’s petit-bourgeois taste and traditionalist furniture, communicating to their contemporary audience a whiff of freedom and societal change.

But the exhibition Sitzen 69 [Sitting 69], which took place in early 1969 at the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts (today’s MAK), contained none of these seating elements which, to us now, seem so characteristic of that era—nor did it contain any of the playful or crazy furniture objects which were to become so emblematic of the alternative and utopian home living concepts of the 1960s. Instead, the exhibition presented an extensive and fine selection of so-called carpenter’s chairs from Scandinavia, Italy, Germany and Austria; these chairs were conceived for either hand or mass production in small and medium-sized operations, and their presentation was intended to provide inspiration to craftsmen, producers and consumers. It was also meant to sensitize its primarily young target audience to the quality of utilitarian items—a mission which the museum’s then-director Wilhelm Mrazek deemed all the more essential in light of his assessment that the balance between tradition and progress in contemporary consumer goods production had become “completely disturbed.” In his foreword to the accompanying exhibition catalogue, Mrazek ascertained that Austria had indeed witnessed noticeable efforts at giving form to everyday objects since the beginning of the postwar economic upturn; however, he considered the tendencies toward imitating existing styles and toward a “modernity that is every bit as questionable” to be indicators of a “complete lack of assurance in questions of taste among all social classes.” In contrast to the cheap and often just superficially designed mass-produced wares of the Wirtschaftswunder [the postwar “Economic Miracle” in Germany and Austria], Mrazek viewed high-quality products such as the carpenters’ chairs in his exhibition as an opportunity to “create that all-too-frequently discounted physical relationship to the things surrounding him which, in the long run, modern man cannot do without.”

Hence, the exhibition Sitzen 69 by no means claimed to offer an overview of the newest trends in international contemporary design, intending much rather—as explicitly formulated—to fulfill the museum’s statutory mission of “encouraging the arts industry and the arts and crafts, and of cultivating taste among our contemporaries.” Exemplary status was accorded in particular to Scandinavian design, which during the postwar period had come to be considered the quintessence of “good form”; particularly in the field of furniture, designs from Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway—and by designers such as Alvar Aalto, Finn Juhl, Kaare Klint, Bruno Mathsson, Ole Wanscher and Hans Wegner—were characterized by pragmatic simplicity. Formal and decorative restraint, the embodiment of traditional values, the unity of form and function, and trust in natural materials were the qualities with which Nordic design was generally associated. Even in the 1960s, furniture design in the only moderately industrialized Scandinavian countries was still very much a matter of close collaboration between designers, craftspeople and small businesses. And following the catastrophic perfection of all that was industrially and technologically possible at the time for the war machinery of World War II, recourse to the warm and natural material of wood—to be had in abundance in these countries—and hand-creation of straightforward, organic shapes for furniture seemed an entirely consistent and logical approach.

Finally, taking Scandinavian furniture as a model made it possible to refer back to Austria’s—and especially Vienna’s—own tradition of furniture design: the exhibition included six chairs from around 1930 designed by Josef Frank and produced by the Viennese company Haus und Garten. Alongside Oskar Strnad, Frank was probably the best-known Austrian interior designer of the Interbellum; in the exhibition catalogue, he was referred to as the “founder of the then-‘new Viennese Style.’” Frank had spoken out against standardized furniture ensembles, total-work-of-art staging and the quest for innovative forms as an end in itself—while also railing against the influence of the Bauhaus aesthetic, which cubic steel furniture he disparaged in his book Architektur als Symbol [Architecture as a Symbol] (1931) with the famous, ironic dictum: “Steel is not a material; steel is a Weltanschauung ... the God that caused iron to form did not desire that there be any wooden furniture.” In Austria at that time, according to the retrospective assessment of curator Franz Windisch-Graetz in the exhibition’s catalogue, there was simply no call to “raise the revolutionary demand for a total new beginning, as propagated by the Bauhaus. Instead, the route of evolution was what proved to be more natural and suitable.” After the architect and designer Frank found it necessary to leave Austria and emigrate to Sweden in 1933 due to intensifying anti-Semitism, he proceeded to contribute important impulses to Scandinavian design. In Vienna, on the other hand, Windisch-Graetz noted that by 1938 at the latest, a process of development was cut off that, at least for a time, had indeed wielded a certain influence internationally: “The Scandinavian—or, more precisely, the Swedish—example shows us how things might have continued here [in Austria] under more favorable conditions. There, Frank was able to continue his work unhindered; through him, the Viennese example continued to have an indirect influence and contributed to the renewal and subsequent golden age of furniture production in Sweden and, indeed, of Scandinavia at large.”

Thus invested with the authority of Josef Frank, the Scandinavian furniture in the exhibition Sitzen 69 was meant to make clear in what direction Viennese furniture could have developed in the postwar period if the tradition of artistically conceived, carpenter-built furniture had not been uprooted—a tradition which, after all, could be traced back—via the new Viennese style of the interwar period and certain turn-of-the-century tendencies such as the close collaboration between artists and craftsmen at the Wiener Werkstätte—all the way to the “Old Viennese Style” of the Biedermeier period. And this exhibition of contemporary Austrian handmade chairs from the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s also attempted to make it clear that, in fact, the prerequisites needed to draw and build upon this heritage were still very much in place: almost all of the nearly thirty Austrian designers, architects and artists introduced by the exhibition had received their training from one of the three main Viennese institutions—either the School of Arts and Crafts, the Academy of Fine Arts or the Polytechnic Academy. Many of the older, already-deceased or retired designers such as Max Fellerer, Oswald Haerdtl, Julius Jirasek, Otto Niedermoser and Franz Schuster had themselves studied with personalities including Oskar Strnad, Josef Hoffmann and Clemens Holzmeister before going on to work as professors at one of these institutions, where they then imparted their abilities to a younger generation of artists and designers including Wilhelm Amberger, Carl Auböck, Wolfgang Haipl, Helmut Otepka and Peter Payer. Others like Carl Appel, Karl Mang, Ernst Plischke, Roland Rainer, Norbert Schlesinger, Johannes Spalt, Eugen Wörle, and—as the only women—Anna-Lülja Praun and Heidemarie Leitner were connected to the abovementioned institutes of higher learning as former students or instructors. Each designer from this last group was represented in the exhibition by at least one piece of furniture.

Sitzen 69, then, must be understood as an appeal to take up the tradition of the outstanding Viennese furniture designs from the century’s first half in accordance with the internationally recognized model embodied by the Scandinavian countries. It was at the same time a programmatically formulated summons to resist contemporary fashions and trends: the idea was that Vienna, which had eschewed the interwar steel-tube obsession of the Bauhaus school, was not to veer off the true path under the influence of a “questionable modernity.” Though the exhibition did explicitly oppose certain types of contemporary consumer culture, this rejection applied neither to rationalistic industrial design per se, as propagated via the product lines of internationally active companies such as Knoll Associates, Hermann Miller, Olivetti and Braun AG, nor to the experimental and provocative “Anti-Design” represented particularly by Italian furniture producers such as Zanotta, Gufram, Arflex, Poltronova and C&B Italia: only a few years prior, the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts had presented Selection 66, a new product line of Austrian office furniture producer Svoboda & Co. that clearly avowed a modern, rationalistic and technological approach in its inclusion of modern design classics by Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer as well as contemporary lamps designed by Achille and Piergiacomo Castiglioni. And the modernist set of upholstered furniture by Arbeitsgruppe 4, reminiscent of furniture designs by Mies van der Rohe and produced since the early 1960’s at the workshops of local furniture producer Wittmann, was even acquired for the museum’s own collection. The radical Anti-Design of the Italian variety, on the other hand, seems—despite its stylistically pioneering role and the media attention given it in Austria—not to have produced much of any real echo, being given serious consideration only by those artists, designers and architects whose own architectural and design-related visions were hardly less radical at the time (one thinks of examples such as the nomadic residential utopias and pneumatically driven furniture experiments by Walter Pichler, Gernot Nalbach, Hans Hollein, Haus-Rucker-Co, Zünd-Up and COOP HIMMELB(L)AU). In the largely down-to-earth and domesticated world of Austrian home design, innovative design and architectural approaches such as these remained just as absent after 1968 as they had been before.

In this light, then, the “questionable modernity” against which the conservative educational agenda of the exhibition Sitzen 69 was directed can be understood as a reference to that continually expanding range of cheap furniture that had come to the fore during the postwar period, furniture that for the most part adhered to the latest fashions but suffered from shoddy workmanship and a short useful life. In his popular books, which were available in German as early as the 1960s, the American social critic Vance Packard repeatedly decried the abasement of product culture entailed by cheap, industrially produced consumer goods. Alongside the lowering of quality standards on the part of the producers, who were employing the principle of planned obsolescence more and more often in order to maintain constant demand for their products, he was particularly critical of the fact that consumers, under the powerful influence of advertising and current fashions, were being manipulated by the mass media to be constantly dissatisfied with their items of daily use. The Austrian Museum of Applied Arts attempted to oppose this fast-intensifying, manipulative way of marketing goods by showing “quality items of daily use” and communicating to its visitors traditional values such as durability, simplicity, functionality, and workmanship appropriate to the materials and products at hand.

In this respect, the exhibition also built on various Austrian initiatives of the postwar period that strove—with great success, in a few cases—to produce high-quality furniture that enabled large groups of consumers to afford something that was in equal measures useful and modern. The furniture range produced by the organization Soziale Wohnkultur [Social Residential Culture], for example, played a decisive role in many households’ ability to renew their furnishings from the floor up—and even as economic conditions of the Wirtschaftswunder began to change, the SW range still found numerous buyers among working-class and upper middle-class consumers alike. Therefore, the overwhelming majority of homes in Austria remained clearly dominated by the postwar atmosphere even at the end of the 1960s: simple and solid furniture made from domestic woods or fiberboard panels, surfaces covered with wood veneer or Resopal (Formica), conventional upholstered furniture covered in cloth, leather or artificial leather, floor lamps with cloth shades, and wallpaper, draperies and bric-a-brac in their traditional colors and patterns were characteristic of the contemporary interior—a living environment where the exhibited carpenter’s chairs of Sitzen 69 most certainly fit in better than such extravagant design pieces as Helmut Bätzner's one-piece and brightly colored plastic chair Bofinger, the futuristically shaped cushioned furniture of a Pierre Paulin, or Peter Ghyczy’s famous Garden Egg Chair.

But it is precisely in comparison with these objects that, in hindsight, the carpenter’s chairs—both Austrian and Scandinavian—shown in the exhibition seem strangely anachronistic: though their high-quality craftsmanship was clear to see, their fabrication and formal language seemed at the same time quite old-fashioned and ignorant of major contemporary developments. The motto “Evolution statt Revolution” [Evolution, not Revolution], which to this day characterizes the lion’s share of Austrian furniture production, stood effectively in opposition to the zeitgeist of the late 1960s. Evidently, however, between the traditional types of artisan products—both old-fashioned stylistic imitations and updated carpenter’s furniture—and the radical design experiments of avant-garde artists and architects, there existed no real livable alternative to the cheap, industrially produced products of consumer society.

Even Walter Pichler’s spacey aluminum fauteuil Galaxy, produced by Svoboda since 1966 and probably the only piece of innovative mass-production furniture design from that period to have received significant notice outside of Austria, was—due to its size, price and, not least, contemporary look—not necessarily all that well suited to domestic homes. But at least this futuristic piece of furniture—which was given several presentations with great media fanfare—saw use in various public institutions: in addition to several buildings of Austria’s national broadcaster ORF, it was also chosen for the Rehabilitationszentrum Meidling (a rehab center) planned by Gustav Peichl and completed in 1968. While pop culture and the protest movement, the alternative scene and the space age did indeed affect the late-1960s Austrian living room, they only did so via that household appliance which, during the postwar period, itself developed into what was undeniably that room’s central piece of furniture: the television.

Bibliography:

Die 60er. Beatles, Pille und Revolte. Exhibition catalogue, Schallaburg, 2010

Neues Wohnen. Wiener Innenraumgestaltung 1918–1938. Exhibition catalogue, Vienna: Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, 1980

Scandinavian Modern Design 1880–1980. Exhibition Catalogue. New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1982

Selection 66. Exhibition Catalogue. Vienna: Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, 1966

Sitzen 69. Exhbition Catalogue. Vienna: Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, 1969

Das SW-Projekt. Möbel. Zeit. Formgefühl. Exhbition Catalogue. Vienna: Bezirksmuseum Josefstadt, 2005

Behal, Vera J. Möbel des Jugendstils. Sammlung des Österreichischen Museums für angewandte Kunst. Munich, 1981

Bony, Anne. Furniture & Interiors of the 1960s. Paris, 2004

Breuer, Gerda, Andrea Peters, and Kerstin Plüm, eds. Die 60er. Positionen des Designs. Cologne, 1999

Frank, Josef. Architektur als Symbol. Vienna,1931

Garner, Philippe. Sixties Design. Cologne, 1996

Herding, Klaus. 1968. Kunst, Kunstgeschichte, Politik. Frankfurt am Main, 2008

Jackson, Lesley. The Sixties. Decade of Design Revolution. Oxford, 1998

Mang, Karl. Geschichte des modernen Möbels. Von der handwerklichen Fertigung zur industriellen Produktion. Stuttgart, 1978

Packard, Vance. Die geheimen Verführer. Düsseldorf, 1958

Packard, Vance. Die große Verschwendung. Düsseldorf, 1961

Ruppert, Wolfgang, ed. Um 1968. Die Repräsentation der Dinge. Marburg, 1998

This text was originally published in conjunction with the exhibition The Sixties. Beatles, Pill and Revolt (2010) at Schallaburg Castle.

But the exhibition Sitzen 69 [Sitting 69], which took place in early 1969 at the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts (today’s MAK), contained none of these seating elements which, to us now, seem so characteristic of that era—nor did it contain any of the playful or crazy furniture objects which were to become so emblematic of the alternative and utopian home living concepts of the 1960s. Instead, the exhibition presented an extensive and fine selection of so-called carpenter’s chairs from Scandinavia, Italy, Germany and Austria; these chairs were conceived for either hand or mass production in small and medium-sized operations, and their presentation was intended to provide inspiration to craftsmen, producers and consumers. It was also meant to sensitize its primarily young target audience to the quality of utilitarian items—a mission which the museum’s then-director Wilhelm Mrazek deemed all the more essential in light of his assessment that the balance between tradition and progress in contemporary consumer goods production had become “completely disturbed.” In his foreword to the accompanying exhibition catalogue, Mrazek ascertained that Austria had indeed witnessed noticeable efforts at giving form to everyday objects since the beginning of the postwar economic upturn; however, he considered the tendencies toward imitating existing styles and toward a “modernity that is every bit as questionable” to be indicators of a “complete lack of assurance in questions of taste among all social classes.” In contrast to the cheap and often just superficially designed mass-produced wares of the Wirtschaftswunder [the postwar “Economic Miracle” in Germany and Austria], Mrazek viewed high-quality products such as the carpenters’ chairs in his exhibition as an opportunity to “create that all-too-frequently discounted physical relationship to the things surrounding him which, in the long run, modern man cannot do without.”

Hence, the exhibition Sitzen 69 by no means claimed to offer an overview of the newest trends in international contemporary design, intending much rather—as explicitly formulated—to fulfill the museum’s statutory mission of “encouraging the arts industry and the arts and crafts, and of cultivating taste among our contemporaries.” Exemplary status was accorded in particular to Scandinavian design, which during the postwar period had come to be considered the quintessence of “good form”; particularly in the field of furniture, designs from Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway—and by designers such as Alvar Aalto, Finn Juhl, Kaare Klint, Bruno Mathsson, Ole Wanscher and Hans Wegner—were characterized by pragmatic simplicity. Formal and decorative restraint, the embodiment of traditional values, the unity of form and function, and trust in natural materials were the qualities with which Nordic design was generally associated. Even in the 1960s, furniture design in the only moderately industrialized Scandinavian countries was still very much a matter of close collaboration between designers, craftspeople and small businesses. And following the catastrophic perfection of all that was industrially and technologically possible at the time for the war machinery of World War II, recourse to the warm and natural material of wood—to be had in abundance in these countries—and hand-creation of straightforward, organic shapes for furniture seemed an entirely consistent and logical approach.

Finally, taking Scandinavian furniture as a model made it possible to refer back to Austria’s—and especially Vienna’s—own tradition of furniture design: the exhibition included six chairs from around 1930 designed by Josef Frank and produced by the Viennese company Haus und Garten. Alongside Oskar Strnad, Frank was probably the best-known Austrian interior designer of the Interbellum; in the exhibition catalogue, he was referred to as the “founder of the then-‘new Viennese Style.’” Frank had spoken out against standardized furniture ensembles, total-work-of-art staging and the quest for innovative forms as an end in itself—while also railing against the influence of the Bauhaus aesthetic, which cubic steel furniture he disparaged in his book Architektur als Symbol [Architecture as a Symbol] (1931) with the famous, ironic dictum: “Steel is not a material; steel is a Weltanschauung ... the God that caused iron to form did not desire that there be any wooden furniture.” In Austria at that time, according to the retrospective assessment of curator Franz Windisch-Graetz in the exhibition’s catalogue, there was simply no call to “raise the revolutionary demand for a total new beginning, as propagated by the Bauhaus. Instead, the route of evolution was what proved to be more natural and suitable.” After the architect and designer Frank found it necessary to leave Austria and emigrate to Sweden in 1933 due to intensifying anti-Semitism, he proceeded to contribute important impulses to Scandinavian design. In Vienna, on the other hand, Windisch-Graetz noted that by 1938 at the latest, a process of development was cut off that, at least for a time, had indeed wielded a certain influence internationally: “The Scandinavian—or, more precisely, the Swedish—example shows us how things might have continued here [in Austria] under more favorable conditions. There, Frank was able to continue his work unhindered; through him, the Viennese example continued to have an indirect influence and contributed to the renewal and subsequent golden age of furniture production in Sweden and, indeed, of Scandinavia at large.”

Thus invested with the authority of Josef Frank, the Scandinavian furniture in the exhibition Sitzen 69 was meant to make clear in what direction Viennese furniture could have developed in the postwar period if the tradition of artistically conceived, carpenter-built furniture had not been uprooted—a tradition which, after all, could be traced back—via the new Viennese style of the interwar period and certain turn-of-the-century tendencies such as the close collaboration between artists and craftsmen at the Wiener Werkstätte—all the way to the “Old Viennese Style” of the Biedermeier period. And this exhibition of contemporary Austrian handmade chairs from the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s also attempted to make it clear that, in fact, the prerequisites needed to draw and build upon this heritage were still very much in place: almost all of the nearly thirty Austrian designers, architects and artists introduced by the exhibition had received their training from one of the three main Viennese institutions—either the School of Arts and Crafts, the Academy of Fine Arts or the Polytechnic Academy. Many of the older, already-deceased or retired designers such as Max Fellerer, Oswald Haerdtl, Julius Jirasek, Otto Niedermoser and Franz Schuster had themselves studied with personalities including Oskar Strnad, Josef Hoffmann and Clemens Holzmeister before going on to work as professors at one of these institutions, where they then imparted their abilities to a younger generation of artists and designers including Wilhelm Amberger, Carl Auböck, Wolfgang Haipl, Helmut Otepka and Peter Payer. Others like Carl Appel, Karl Mang, Ernst Plischke, Roland Rainer, Norbert Schlesinger, Johannes Spalt, Eugen Wörle, and—as the only women—Anna-Lülja Praun and Heidemarie Leitner were connected to the abovementioned institutes of higher learning as former students or instructors. Each designer from this last group was represented in the exhibition by at least one piece of furniture.

Sitzen 69, then, must be understood as an appeal to take up the tradition of the outstanding Viennese furniture designs from the century’s first half in accordance with the internationally recognized model embodied by the Scandinavian countries. It was at the same time a programmatically formulated summons to resist contemporary fashions and trends: the idea was that Vienna, which had eschewed the interwar steel-tube obsession of the Bauhaus school, was not to veer off the true path under the influence of a “questionable modernity.” Though the exhibition did explicitly oppose certain types of contemporary consumer culture, this rejection applied neither to rationalistic industrial design per se, as propagated via the product lines of internationally active companies such as Knoll Associates, Hermann Miller, Olivetti and Braun AG, nor to the experimental and provocative “Anti-Design” represented particularly by Italian furniture producers such as Zanotta, Gufram, Arflex, Poltronova and C&B Italia: only a few years prior, the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts had presented Selection 66, a new product line of Austrian office furniture producer Svoboda & Co. that clearly avowed a modern, rationalistic and technological approach in its inclusion of modern design classics by Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer as well as contemporary lamps designed by Achille and Piergiacomo Castiglioni. And the modernist set of upholstered furniture by Arbeitsgruppe 4, reminiscent of furniture designs by Mies van der Rohe and produced since the early 1960’s at the workshops of local furniture producer Wittmann, was even acquired for the museum’s own collection. The radical Anti-Design of the Italian variety, on the other hand, seems—despite its stylistically pioneering role and the media attention given it in Austria—not to have produced much of any real echo, being given serious consideration only by those artists, designers and architects whose own architectural and design-related visions were hardly less radical at the time (one thinks of examples such as the nomadic residential utopias and pneumatically driven furniture experiments by Walter Pichler, Gernot Nalbach, Hans Hollein, Haus-Rucker-Co, Zünd-Up and COOP HIMMELB(L)AU). In the largely down-to-earth and domesticated world of Austrian home design, innovative design and architectural approaches such as these remained just as absent after 1968 as they had been before.

In this light, then, the “questionable modernity” against which the conservative educational agenda of the exhibition Sitzen 69 was directed can be understood as a reference to that continually expanding range of cheap furniture that had come to the fore during the postwar period, furniture that for the most part adhered to the latest fashions but suffered from shoddy workmanship and a short useful life. In his popular books, which were available in German as early as the 1960s, the American social critic Vance Packard repeatedly decried the abasement of product culture entailed by cheap, industrially produced consumer goods. Alongside the lowering of quality standards on the part of the producers, who were employing the principle of planned obsolescence more and more often in order to maintain constant demand for their products, he was particularly critical of the fact that consumers, under the powerful influence of advertising and current fashions, were being manipulated by the mass media to be constantly dissatisfied with their items of daily use. The Austrian Museum of Applied Arts attempted to oppose this fast-intensifying, manipulative way of marketing goods by showing “quality items of daily use” and communicating to its visitors traditional values such as durability, simplicity, functionality, and workmanship appropriate to the materials and products at hand.

In this respect, the exhibition also built on various Austrian initiatives of the postwar period that strove—with great success, in a few cases—to produce high-quality furniture that enabled large groups of consumers to afford something that was in equal measures useful and modern. The furniture range produced by the organization Soziale Wohnkultur [Social Residential Culture], for example, played a decisive role in many households’ ability to renew their furnishings from the floor up—and even as economic conditions of the Wirtschaftswunder began to change, the SW range still found numerous buyers among working-class and upper middle-class consumers alike. Therefore, the overwhelming majority of homes in Austria remained clearly dominated by the postwar atmosphere even at the end of the 1960s: simple and solid furniture made from domestic woods or fiberboard panels, surfaces covered with wood veneer or Resopal (Formica), conventional upholstered furniture covered in cloth, leather or artificial leather, floor lamps with cloth shades, and wallpaper, draperies and bric-a-brac in their traditional colors and patterns were characteristic of the contemporary interior—a living environment where the exhibited carpenter’s chairs of Sitzen 69 most certainly fit in better than such extravagant design pieces as Helmut Bätzner's one-piece and brightly colored plastic chair Bofinger, the futuristically shaped cushioned furniture of a Pierre Paulin, or Peter Ghyczy’s famous Garden Egg Chair.

But it is precisely in comparison with these objects that, in hindsight, the carpenter’s chairs—both Austrian and Scandinavian—shown in the exhibition seem strangely anachronistic: though their high-quality craftsmanship was clear to see, their fabrication and formal language seemed at the same time quite old-fashioned and ignorant of major contemporary developments. The motto “Evolution statt Revolution” [Evolution, not Revolution], which to this day characterizes the lion’s share of Austrian furniture production, stood effectively in opposition to the zeitgeist of the late 1960s. Evidently, however, between the traditional types of artisan products—both old-fashioned stylistic imitations and updated carpenter’s furniture—and the radical design experiments of avant-garde artists and architects, there existed no real livable alternative to the cheap, industrially produced products of consumer society.

Even Walter Pichler’s spacey aluminum fauteuil Galaxy, produced by Svoboda since 1966 and probably the only piece of innovative mass-production furniture design from that period to have received significant notice outside of Austria, was—due to its size, price and, not least, contemporary look—not necessarily all that well suited to domestic homes. But at least this futuristic piece of furniture—which was given several presentations with great media fanfare—saw use in various public institutions: in addition to several buildings of Austria’s national broadcaster ORF, it was also chosen for the Rehabilitationszentrum Meidling (a rehab center) planned by Gustav Peichl and completed in 1968. While pop culture and the protest movement, the alternative scene and the space age did indeed affect the late-1960s Austrian living room, they only did so via that household appliance which, during the postwar period, itself developed into what was undeniably that room’s central piece of furniture: the television.

Bibliography:

Die 60er. Beatles, Pille und Revolte. Exhibition catalogue, Schallaburg, 2010

Neues Wohnen. Wiener Innenraumgestaltung 1918–1938. Exhibition catalogue, Vienna: Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, 1980

Scandinavian Modern Design 1880–1980. Exhibition Catalogue. New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1982

Selection 66. Exhibition Catalogue. Vienna: Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, 1966

Sitzen 69. Exhbition Catalogue. Vienna: Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, 1969

Das SW-Projekt. Möbel. Zeit. Formgefühl. Exhbition Catalogue. Vienna: Bezirksmuseum Josefstadt, 2005

Behal, Vera J. Möbel des Jugendstils. Sammlung des Österreichischen Museums für angewandte Kunst. Munich, 1981

Bony, Anne. Furniture & Interiors of the 1960s. Paris, 2004

Breuer, Gerda, Andrea Peters, and Kerstin Plüm, eds. Die 60er. Positionen des Designs. Cologne, 1999

Frank, Josef. Architektur als Symbol. Vienna,1931

Garner, Philippe. Sixties Design. Cologne, 1996

Herding, Klaus. 1968. Kunst, Kunstgeschichte, Politik. Frankfurt am Main, 2008

Jackson, Lesley. The Sixties. Decade of Design Revolution. Oxford, 1998

Mang, Karl. Geschichte des modernen Möbels. Von der handwerklichen Fertigung zur industriellen Produktion. Stuttgart, 1978

Packard, Vance. Die geheimen Verführer. Düsseldorf, 1958

Packard, Vance. Die große Verschwendung. Düsseldorf, 1961

Ruppert, Wolfgang, ed. Um 1968. Die Repräsentation der Dinge. Marburg, 1998

This text was originally published in conjunction with the exhibition The Sixties. Beatles, Pill and Revolt (2010) at Schallaburg Castle.

Media

Walter Pichler: Armchair “Galaxy”

Vienna, 1966

Manufacture: R. Svoboda & Co

Aluminum, foam upholstery coated with synthetic fiber

H 2883 / 1987

Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini and Franco Teodoro: Sacco

1968

Manufacture: Zanotta, Nova Milanese, Italy

Vinyl, expanded polystyrene pellets

H 3362 / 2006, donation Zanotta

Helmut Bätzner: Modell BA 1171 „Bofinger“

Germany, 1964-65

Manufacture: Wilhelm Bofinger KG, Ilsfeld/Heilbronn, Germany

Polyester resin, glass-fiber reinforced

Verner Panton: Panton

1967

Manufacture: Herman Miller / Vitra, 1968-1971

Polyurethane

H 2898 / 1987, donation Inge Zerunian, Vienna

Pierre Paulin: Model 577 (“Tongue”)

1967

Manufacture: Artifort, Maastricht

Foam upholstery on metal frame, fabric cover

H 2832 / 1986, donation Franziska Helmreich, Vienna

Peter Ghyczy: Seating furniture “Garden Egg”

1968

Manufacture: Chemiekombinat Schwarzheide-Senftenberg, East Germany, 1974

Synthetic material, fabric cover

H 3214 / 1995

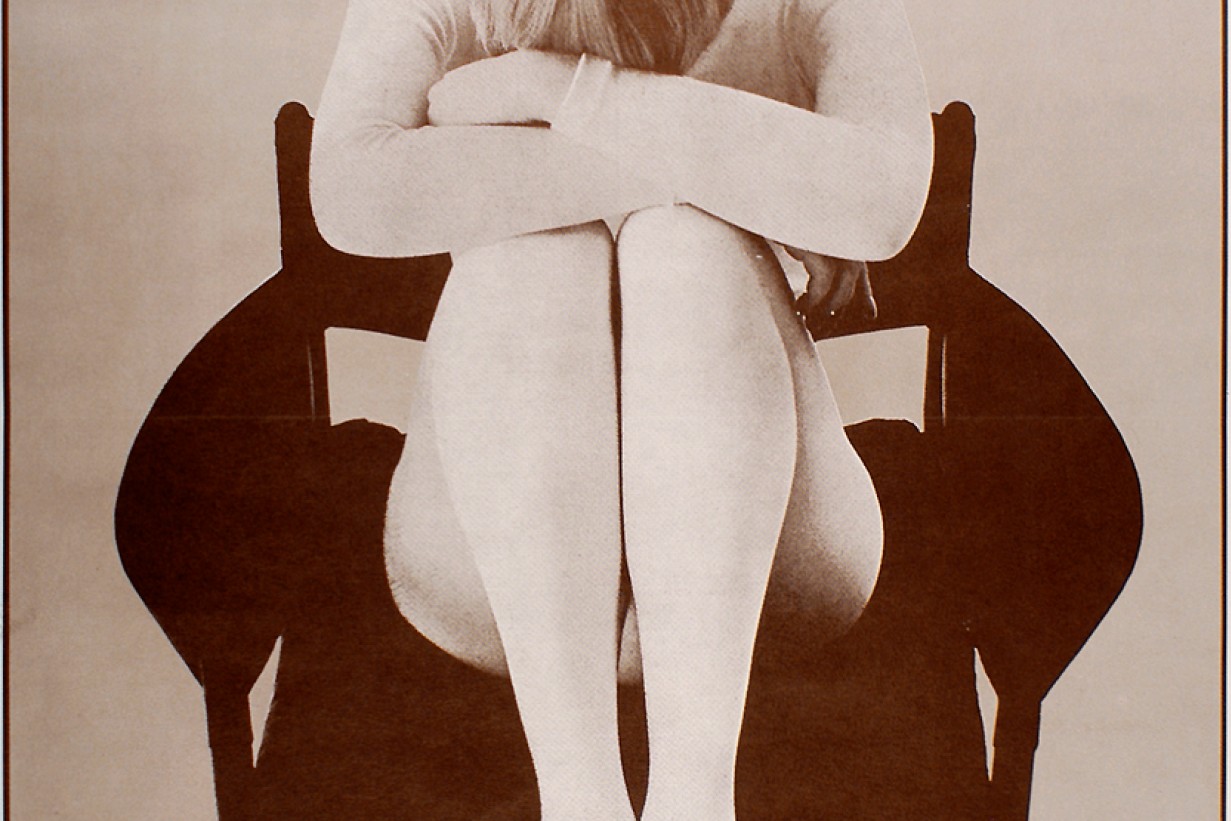

Christoph Schartelmüller: Sitzen 69 [Seating 69]

Vienna, 1969

Poster for the exhibition at the Austrian Museum of Applied Art

Print: G. Gistel & Cie

Offset print on paper

PI 10022 / 1969

Hans J. Wegner: Armchair

Odense, Denmark, 1950

Manufacture: Carl Hansen & Søn AS

Solid oak, string mesh

H 2125

Rudolf Frank: Chair

Steinheim/Murr, Württemberg, West Germany, 1963

Manufacture: Lukas Schnaidt

Solid cherry, wickerwork (Rattan)

H 2127

Yngve Ekström: Armchair

Vaggeryd, Sweden, 1955

Manufacture: SWEDESE Möbler AB

Oak, ash, and walnut, partly laminated, partly solid, leather covering

H 2136

Otto Niedermoser: School Chair

Vienna, 1964

Prototype: Versuchswerkstätte der Meisterklasse für Innenarchitektur und Möbelbau, Akademie für angewandte Kunst, Wien [Workshop of the master class for interior design and cabinetry at the Academy of Applied Arts, Vienna]

Frame: solid beechwood, damped, white finish

Seat: raised plywood, black

![Christoph Schartelmüller: Sitzen 69 [Seating 69]](/jart/prj3/mak-resp/images/cache/3d4051f70ee599a9cc06e9fe1a4ea51b/0x63F2ACBC586C3DDB85071082B98BB9CA.jpeg)